History

Principal Commanders: George B. McClellan and Joseph E. Johnston, commanders of the Union and Confederate armies in the Peninsula Campaign.

CS. Forces: A.P Hill Brigade of Virginia Troops, James Longstreet’s Division

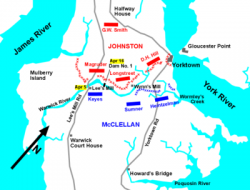

Description: On April 4, 1862, the Union Army pushed through Magruder's initial line of defense but the following day encountered his more effective Warwick Line. The nature of the terrain made it difficult to determine the exact disposition of the Confederate forces. A victim of faulty intelligence, McClellan estimated that the Confederates had 40,000 troops in the defensive line and that Johnston was expected to arrive quickly with an additional 60,000. Magruder, an amateur actor before the war, exacerbated McClellan's confusion by moving infantry and artillery in a noisy, ostentatious manner to make the defenders seem a much larger forces than their actual numbers.

The Union IV Corps first encountered the right flank of Magruder's line on April 5 at Lee's Mill, its earthwork defenses manned by the division of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws. The 7th Maine Infantry Regiment deployed as skirmishers and stopped about 1,000 yards before the fortifications, where they were soon joined by the brigade of Brig. Gen. John Davidson and artillery. An artillery duel raged for several hours while Keyes ordered reconnaissance and additional units arrived, but there was no infantry fighting. On April 6, men from the 6th Maine and 5th Wisconsin, under the command of Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, performed reconnaissance around Dam Number One, where Magruder had widened the Warwick to create a water obstacle nearby. They drove off the Confederate pickets and took some prisoners. Hancock considered this area a weak spot in the line, but orders from McClellan prevented any exploitation. Keyes, deceived by Magruder's theatrical troop movements, believed that the Warwick Line fortifications could not be carried by assault and so informed McClellan.

To the amazement of the Confederates, and the dismay of President Abraham Lincoln, McClellan chose not to attack without more reconnaissance and ordered his army to entrench in works parallel to Magruder's and besiege Yorktown. McClellan reacted to Keyes's report, as well as to reports of enemy strength near the town of Yorktown, but he also received word that the I Corps, under Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell, would be withheld for the defense of Washington, instead of joining him on the Peninsula as McClellan had planned. For the next 10 days, McClellan's men dug while Magruder steadily received reinforcements. By mid April, Magruder commanded 35,000 men, barely enough to defend his line.

Although McClellan doubted his numeric superiority over the enemy, he had no doubts about the superiority of his artillery. The siege preparations at Yorktown consisted of 15 batteries with more than 70 heavy guns, including two 200-pounder Parrotts and 12 100-pound Parrots, with the rest of the rifled pieces divided between 20-pounder and 30-pounder Parrotts and 4.5-inch Rodman siege rifles. These were augmented by 41 mortars, ranging in size from 8 inches to 13-inch seacoast mortars, which weighed over 10 tons and fired shells weighing 220 pounds. When fired in unison, these batteries would deliver over 7,000 pounds of ordnance onto the enemy positions with each volley.

As the armies dug in, Union Army Balloon Corps aeronaut Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe used two balloons, the Constitution and the Intrepid, to perform aerial observation. On April 11, Intrepid carried Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter, a division commander of the III Corps, aloft, but unexpected winds sent the balloon over enemy lines, causing great consternation in the Union

command before other winds returned him to safety. Confederate Captain John Bryan suffered a similar wind mishap in a hot air balloon over the Yorktown lines.

Warwick Line April 1862

CS. Forces: A.P Hill Brigade of Virginia Troops, James Longstreet’s Division

Description: On April 4, 1862, the Union Army pushed through Magruder's initial line of defense but the following day encountered his more effective Warwick Line. The nature of the terrain made it difficult to determine the exact disposition of the Confederate forces. A victim of faulty intelligence, McClellan estimated that the Confederates had 40,000 troops in the defensive line and that Johnston was expected to arrive quickly with an additional 60,000. Magruder, an amateur actor before the war, exacerbated McClellan's confusion by moving infantry and artillery in a noisy, ostentatious manner to make the defenders seem a much larger forces than their actual numbers.

The Union IV Corps first encountered the right flank of Magruder's line on April 5 at Lee's Mill, its earthwork defenses manned by the division of Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws. The 7th Maine Infantry Regiment deployed as skirmishers and stopped about 1,000 yards before the fortifications, where they were soon joined by the brigade of Brig. Gen. John Davidson and artillery. An artillery duel raged for several hours while Keyes ordered reconnaissance and additional units arrived, but there was no infantry fighting. On April 6, men from the 6th Maine and 5th Wisconsin, under the command of Brig. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock, performed reconnaissance around Dam Number One, where Magruder had widened the Warwick to create a water obstacle nearby. They drove off the Confederate pickets and took some prisoners. Hancock considered this area a weak spot in the line, but orders from McClellan prevented any exploitation. Keyes, deceived by Magruder's theatrical troop movements, believed that the Warwick Line fortifications could not be carried by assault and so informed McClellan.

To the amazement of the Confederates, and the dismay of President Abraham Lincoln, McClellan chose not to attack without more reconnaissance and ordered his army to entrench in works parallel to Magruder's and besiege Yorktown. McClellan reacted to Keyes's report, as well as to reports of enemy strength near the town of Yorktown, but he also received word that the I Corps, under Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell, would be withheld for the defense of Washington, instead of joining him on the Peninsula as McClellan had planned. For the next 10 days, McClellan's men dug while Magruder steadily received reinforcements. By mid April, Magruder commanded 35,000 men, barely enough to defend his line.

Although McClellan doubted his numeric superiority over the enemy, he had no doubts about the superiority of his artillery. The siege preparations at Yorktown consisted of 15 batteries with more than 70 heavy guns, including two 200-pounder Parrotts and 12 100-pound Parrots, with the rest of the rifled pieces divided between 20-pounder and 30-pounder Parrotts and 4.5-inch Rodman siege rifles. These were augmented by 41 mortars, ranging in size from 8 inches to 13-inch seacoast mortars, which weighed over 10 tons and fired shells weighing 220 pounds. When fired in unison, these batteries would deliver over 7,000 pounds of ordnance onto the enemy positions with each volley.

As the armies dug in, Union Army Balloon Corps aeronaut Professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe used two balloons, the Constitution and the Intrepid, to perform aerial observation. On April 11, Intrepid carried Brig. Gen. Fitz John Porter, a division commander of the III Corps, aloft, but unexpected winds sent the balloon over enemy lines, causing great consternation in the Union

command before other winds returned him to safety. Confederate Captain John Bryan suffered a similar wind mishap in a hot air balloon over the Yorktown lines.

Warwick Line April 1862

On April 16, the Union probed the defensive line at Dam No. 1, the point on the Warwick River near Lee's Mill where Hancock had reported a potential weakness on April 6. After the brief skirmish with Hancock's men, Magruder realized the weakness of his position and ordered it strengthened. Three regiments under Brig. Gen. Howell Cobb, with six other regiments nearby, were improving their position on the west bank of the river overlooking the dam. McClellan became concerned that this strengthening might impede his installation of siege batteries. His order to Brig. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith, a division commander in the IV Corps, was to avoid a general engagement, but to "hamper the enemy" in completing their defensive works.

Following an artillery bombardment at 8 a.m., Brig. Gen. William T. H. Brooks and his Vermont Brigade sent skirmishers forward to fire on the Confederates. In a visit to the front, McClellan told Smith to cross the river if it appeared the Confederates were withdrawing, a movement that was already underway by early afternoon. At 3 p.m., four companies of the 3rd Vermont Infantry crossed the dam and routed the remaining defenders. Behind the lines, Cobb organized a defense with his brother, Colonel Thomas Cobb of the Georgia Legion, and attacked the Vermonters, who had occupied the Confederate rifle pits. In battle, drummer Julian Scott made several trips across the fire-swept creek in order to assist in bringing off wounded soldiers. Later he was awarded the Medal of Honor, along with First Sergeant Edward Holton and Captain Samuel E. Pingree.

Unable to obtain reinforcements, the Vermont companies withdrew across the dam, suffering casualties as they retreated. At about 5 p.m., Baldy Smith ordered the 6th Vermont to attack Confederate positions downstream from the dam while the 4th Vermont demonstrated at the dam itself. This maneuver failed as the 6th Vermont came under heavy Confederate fire and were forced to withdraw. Some of the wounded men were drowned as they fell into the shallow pond behind the dam.

From a Union perspective, the action at Dam No. 1 was pointless, but it cost them casualties of 35 dead and 121 wounded; the Confederate casualties were between 60 and 75. Baldy Smith, who was thrown from his unruly horse twice during action, was accused of drunkenness on duty, but a congressional investigation found the allegation to be groundless.

For the remainder of April, the Confederates, now at 57,000 and under the direct command of Johnston, improved their defenses while McClellan undertook the laborious process of transporting and placing massive siege artillery batteries, which he planned to deploy on May 5. Johnston knew that the impending bombardment would be difficult to withstand, so began sending his supply wagons in the direction of Richmond on May 3. Escaped slaves reported that fact to McClellan, who refused to believe them. He was convinced that an army whose strength he estimated as high as 120,000 would stay and fight. On the evening of May 3, the Confederates launched a brief bombardment of their own and then fell silent. Early the next morning, Heintzelman ascended in an observation balloon and found that the Confederate earthworks were empty.

McClellan was stunned by the news. He sent cavalry under Brig. Gen. George Stoneman in pursuit and ordered Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin's division to reboard Navy transports, sail up the York River, and cut off Johnson's retreat. The stage was set for the subsequent Battle of Williamsburg.

Following an artillery bombardment at 8 a.m., Brig. Gen. William T. H. Brooks and his Vermont Brigade sent skirmishers forward to fire on the Confederates. In a visit to the front, McClellan told Smith to cross the river if it appeared the Confederates were withdrawing, a movement that was already underway by early afternoon. At 3 p.m., four companies of the 3rd Vermont Infantry crossed the dam and routed the remaining defenders. Behind the lines, Cobb organized a defense with his brother, Colonel Thomas Cobb of the Georgia Legion, and attacked the Vermonters, who had occupied the Confederate rifle pits. In battle, drummer Julian Scott made several trips across the fire-swept creek in order to assist in bringing off wounded soldiers. Later he was awarded the Medal of Honor, along with First Sergeant Edward Holton and Captain Samuel E. Pingree.

Unable to obtain reinforcements, the Vermont companies withdrew across the dam, suffering casualties as they retreated. At about 5 p.m., Baldy Smith ordered the 6th Vermont to attack Confederate positions downstream from the dam while the 4th Vermont demonstrated at the dam itself. This maneuver failed as the 6th Vermont came under heavy Confederate fire and were forced to withdraw. Some of the wounded men were drowned as they fell into the shallow pond behind the dam.

From a Union perspective, the action at Dam No. 1 was pointless, but it cost them casualties of 35 dead and 121 wounded; the Confederate casualties were between 60 and 75. Baldy Smith, who was thrown from his unruly horse twice during action, was accused of drunkenness on duty, but a congressional investigation found the allegation to be groundless.

For the remainder of April, the Confederates, now at 57,000 and under the direct command of Johnston, improved their defenses while McClellan undertook the laborious process of transporting and placing massive siege artillery batteries, which he planned to deploy on May 5. Johnston knew that the impending bombardment would be difficult to withstand, so began sending his supply wagons in the direction of Richmond on May 3. Escaped slaves reported that fact to McClellan, who refused to believe them. He was convinced that an army whose strength he estimated as high as 120,000 would stay and fight. On the evening of May 3, the Confederates launched a brief bombardment of their own and then fell silent. Early the next morning, Heintzelman ascended in an observation balloon and found that the Confederate earthworks were empty.

McClellan was stunned by the news. He sent cavalry under Brig. Gen. George Stoneman in pursuit and ordered Brig. Gen. William B. Franklin's division to reboard Navy transports, sail up the York River, and cut off Johnson's retreat. The stage was set for the subsequent Battle of Williamsburg.